FOOD DESERTS – SCARCITY IN THE LAND OF PLENTY

The phrase “food desert” may sound like something from dystopian science fiction movie, but living in a food desert is a reality that a surprising number of Americans face every day. The term was first coined by the Scottish Nutrition Task Force in 1995 and first introduced to the US via the 2008 Farm Bill (Food Conservation and Energy Act of 2008).

Food deserts are areas that lack access to affordable fresh meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and other foods that make up a healthy diet; they are a major factor in overall food insecurity in our nation. The USDA defines a food desert as having a poverty rate of 20% or greater, and by how close residents are to supermarkets. In urban food deserts, people live more than a mile away from a supermarket. In rural food deserts, distance to a grocery store is greater than 10 miles.

A 2012 USDA report showed that the main characteristics of food desert areas are: a very large or very sparse population, low income, high levels of unemployment, inadequate access to transportation, and a low number of food retailers providing fresh produce at affordable prices.

Food desert residents usually struggle with a combination of these factors and there are differing schools of thought regarding food deserts and their true effects.

Availability, Accessibility, and Affordability Are Issues—Or Are They?

The most wide-spread thinking holds that residents of food deserts have difficulty juggling availability, accessibility, and affordability of healthy food to the extent that their health suffers. Without ready access to full-service supermarkets, it can also be difficult for those with dietary restrictions to find appropriate food to fit their cultural or health needs.

Even in cases where healthy food is readily available, the cost can be a major barrier for consumers. In 2013, a comprehensive study was done that compiled data from 27 studies in 10 countries. It showed that the cost of healthy food is about $1.50 more per day than less healthy options, which makes for $550 per person per year. The total increase for a family of four is over $2,000, which can be a substantial amount for low-income households.

In 2015, the USDA found that 2.1 million households both lived in a food desert and lacked access to a vehicle. Thus, the thinking goes, even if those people can afford to buy healthy foods, it can be difficult for them to get to a grocery store, and they may therefore rely more heavily on fast-food restaurants and convenience stores.

A paradox exists in urban food deserts: amidst a scarcity of healthy food, there is a high percentage of obese people, due to the increased consumption of less-healthy foods. The result is a prevalence of obesity and other diet-related health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease in those areas. A study of Chicago neighborhoods found that deaths from diabetes in food deserts were actually double those in areas with relatively easy access to grocery stores.

Conversely, a study by the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) found that association between food deserts and adverse outcomes is largely driven by low area income, not poor access to food.

Further, research from New York University (NYU) showed: “between 2004 and 2016, more than a thousand supermarkets opened nationwide in neighborhoods around the country that had previously been food deserts. NYU studied the grocery purchases of about 10,000 households in those neighborhoods. While it’s true that these households buy less healthy groceries than people in wealthier neighborhoods, they do not start buying healthier groceries after a new supermarket opened. Instead, we find that people shop at the new supermarket, but they buy the same kinds of groceries they had been buying before.”

In addition, the study also stated, “the average American travels 5.2 miles to shop, and 90 percent of shopping trips are made by car. In fact, low-income households are not much different—they travel an average of 4.8 miles. Since we’re traveling that far, we tend to shop in supermarkets even if there isn’t one down the street. Even people who live in zip codes with no supermarket still buy 85 percent of their groceries from supermarkets.”

Considering that there are countless educational resources for people who wish to learn how to make good dietary choices, it would seem that the biggest factor in individual health simply boils down to personal choice. This is not to belittle the effects of insufficient nutrition, which tends to have the heaviest effect on children in low-income areas.

Long Term Effects Go Far Beyond Nutrition

Nutrition or the lack thereof affects more than physical health. Studies have shown that children who struggle with poor nutrition are more likely to have social and behavioral problems in school. This can lead to students dropping out of school and other types of failed education, which very often result in economic failures later in life.

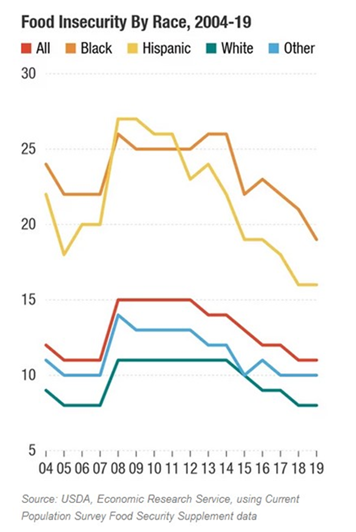

The long-term economic cycle in areas deemed to be food deserts are vicious. Multi-generational families in food deserts tend to experience decreasing wealth, which leads to businesses leaving the area, which means fewer employment opportunities, which leads to even further reduced wealth. When new stores open, they open in areas of higher income to reduce the risk of their investment. The decreased buying power of customers in low-income areas and the threat of higher crime rates—whether real or perceived—tend to push businesses away. Some go so far as to label the results “food apartheid,” since food insecurity affects minority groups to a greater degree.

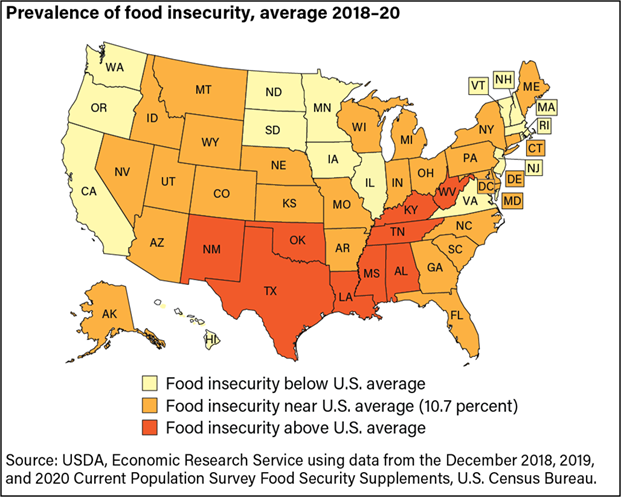

Food Insecurity Most Prevalent in Southern States

It follows, then that the highest concentration of food insecure communities are located in areas with higher populations of minority groups.

The USDA has calculated that there are 9,245 total census tracts in the United States which fall within the parameters to be considered a food desert. The USDA website states: “a census tract is a small, relatively permanent subdivision of a county that usually contains between 1,000 and 8,000 people but generally averages around 4,000 people.” Rural counties make up 63% of total counties in the country, but they make up 87% of counties with the highest rates of food insecurity.

A December 2020 USDA survey showed that 10.5% of total US households were food insecure, with 6.6% being at low food security status and 3.9% at very low food security status. These percentages account for 38.3 million people, including 6.1 million children. Of those children, 584,000 live in households that experience very low food security.

This particular survey defined low food-insecure households as being able to obtain enough food to mostly maintain their eating patterns, or to reduce food intake by eating less varied diets. This group was also able to rely on assistance from federal programs and local food pantries.

Very low food security status was defined by having the normal eating patterns of one or more household members disrupted by food scarcity, and by cases of overall food intake being reduced due to lack of money and other resources to obtain food.

No Easy Answers

Considering the differing schools of thought on the issue, is not clear how geographic location truly affects food insecurity, or what measures to alleviate it are most effective.

Ohio University writes, “Dealing with food deserts across the United States is a complex issue with no easy solutions. It is difficult for communities and cities to simply build more grocery stores, develop more transit options, or find ways to help individuals generate more income to purchase healthy foods.”

Conversely, New York University stated: “Over the past decade, federal and local governments in the United States have spent hundreds of millions of dollars encouraging grocery stores to open in food deserts. The federal Healthy Food Financing Initiative has leveraged over $1 billion in financing for grocers in under-served areas. …Meanwhile, cities such as Houston and Denver have sought to institute related measures at the local level.”

Some mistakenly believe that subsidies for commodities like corn and soy work to lower the prices of foods that are more processed and less healthy. Some blame the market-driven polices that focus on turning out inexpensive, high-volume, highly processed food products for maximum industry profit. One school of thought holds that placing a “sin tax” on less healthy foods would discourage their purchase.

While a variety of programs exist to help with food insecurity, they can only do so much, especially considering that inflation, supply chain issues, and food shortages are currently impacting all Americans. In fact, researchers at Northwestern University found that food insecurity more than doubled because of the covid-19 pandemic, affecting up to 23% of households. Of course, the already precarious situation of the millions of food-insecure people has been greatly exacerbated by the current state of affairs in our nation.

Through the tangled web of issues surrounding food insecurity, one thing is abundantly clear: our nation’s food producers are more important than ever and we must do all we can to protect and support them.

Links:

Information about Prop 12 in California HERE HERE HERE

Information about Inflation and Food Prices HERE

ELD Mandate Can Impact Inflation HERE